In Movies and Circuses

by James Searles

This is based on a article by Fred D. Pfening, Jr, former president of the Circus Historical Society.

I have expanded upon the original article, adding more information where I felt it was needed and tried to explain further what was not covered. Information about horses was added because of their importance in Western movies. The Pfening article was given to me by Duke Shumow. Duke had owned two movie theaters in Chicago. His dad was Jack Shumow, an MGM executive. I might have taken some advantage of Duke, who was then way up in years. I got a very old full page article on elephants that was frail. Duke had to drive it up to the Circus Museum at Baraboo, Wisconsin. Two weeks later I got a circus movie poster—too frail to mail. Duke again drove it up to Baraboo. We have some of the Joseph Brown photo collection going back to 1897. One of the glass sheet photos was of a circus coming into Milwaukee. I had some medium level at best shots taken off the glass plates that Duke used in Baraboo. We listed them under Duke’s name. I added in a bit more about the movies and the horses – can’t have a circus without horses. The horses that the cowboys loved got star billing both in posters and events. The article is for reference only. Donations to the Baraboo Circus Museum help to preserve a way of life fast disappearing. Better yet, head over to the Baraboo Circus Museum (Baraboo, WI) this summer and catch the circus act. —Author

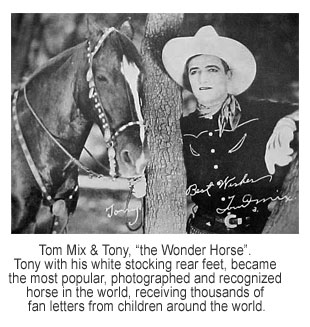

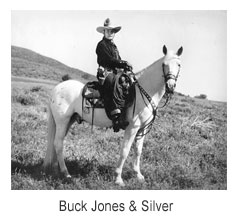

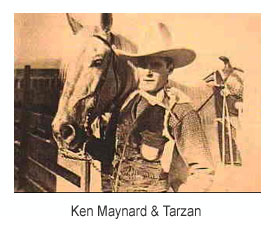

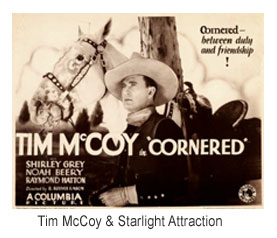

At the end of the 1920s, “outdoor” under-canvas shows began hiring well known motion picture western stars as feature attractions. During the golden age of the Hollywood western films in the 1920s and 1930s, the five big stars were Tom Mix, Buck Jones, Ken Maynard, Hoot Gibson and Tim McCoy. All were featured with circuses. A number of them worked with circuses before their film careers started. Some started their own circus or wild west show. Other than Mix all their shows failed quickly.

Tom Mix (1890-1940) Mix was born into a relatively poor logging family in Mix Run, PA. He spent his childhood leaning to ride horses and working on the local farm. He had dreams of being in the circus and was rumored to have been caught by his parents practicing knife-throwing tricks against a wall, using his sister as an assistant. Aft er working a variety of odd jobs in the Oklahoma Territory, Mix found employment at the Miller Brothers 101 ranch, reportedly the largest ranching business in the United States and covering 101,000 acres, hence its name. He stood out as a skilled horseman and expert shot, winning the 1909 national Riding and Rodeo Championship.

er working a variety of odd jobs in the Oklahoma Territory, Mix found employment at the Miller Brothers 101 ranch, reportedly the largest ranching business in the United States and covering 101,000 acres, hence its name. He stood out as a skilled horseman and expert shot, winning the 1909 national Riding and Rodeo Championship.

Tom Mix at the Circus:

In 1909 Tom Mix was with W. S. Dickey’s Circle C Ranch Wild West show. Dickey had a connection with the Selig Polyscope Company, an early producer of western films. Mix made his first film for Selig in 1909. When the Selig Studios closed, Mix went to William Fox Productions. He made a reported 336 films between 1910 and 1935, all but nine were silent features. He was Hollywood’s first Western mega-star and is noted as having helped define the genre for all cowboy stars who followed. Over half of the movies were made by Selig and Fox, but he also worked for Universal, Film Box Office and Mascot. In his early career he worked during the summers with the Kit Carson Buffalo Ranch Wild West and the Young Buffalo Wild West. He survived the change to talking pictures and made his last film in 1935 for the poverty row Mascot Pictures. In the 1920s he was one of the leading box office stars in Hollywood. In 1929 he went to work for the Sells-Floto Circus and remained there for three years. In 1934 he joined the Sam B. Dill motorized circus. In 1935 Mix bought the show and continued the Tom Mix Circus through 1938. At its height the show was the largest and most successful circus on the road. He made a number of successful tours of Europe before being killed in a car crash in 1940.

Charles Frederick Gebhard (Buck Jones 1981-1942) was with Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West in 1913 and Gollmar Brothers Circus in 1914. Adopting the name Charles Jones, he made his first film for Fox in 1918 later becoming “Buck Jones”. He produced and directed many of the films in which he appeared. During his career Jones appeared in nearly 200 movies produced by Fox, Columbia, Universal, Paramount, Republic and Monogram. He last film was for Monogram Pictures in 1941.

Buck Jones at the Circus:

In 1929 he organized the Buck Jones Wild West and Round Up Days. Monty Montana, a radio and motion picture personality, was with the Jones show. It opened on May 16 and lasted until July, when his business partner absconded with all the show’s money, leaving Jones high and dry. Jones quickly joined the Robbins Brothers Circus to finish the season. He died in Boston in the 1942 Coconut Grove night club fire.

Ken Maynard (1891-1978) Working at carnivals and circuses starting at age 16, Maynard became an accomplished horseman. As a young man, he performed in rodeos and was a trick rider with the Kit Carson Buffalo Ranch Wild West in 1913 and Ringling Brothers in 1914. He first appeared in 1923 (for William Fox) and in addition to acting, he also did stunt work. His hors emanship and rugged good looks made Maynard a cowboy star. His white stallion, "Tarzan", also became famous. He became one of the first singing cowboys with Columbia Records, recording two songs, "The Lone Star Trail" and "The Cowboy's Lament". With his white cowboy hat, fancy shirt, and pair of six-shooters, from the 1920s to the mid-1940s, Maynard appeared in more than 90 films. However, his alcoholism severely impacted his life and his career ended in 1944. He made appearances at state fairs and rodeos. He then owned a small circus operation featuring rodeo riders but eventually lost it to creditors. The significant amount of money he had earned vanished, and he lived a desolate life in a rundown mobile home. During these years, Maynard was supported by an unknown benefactor, long thought to be Gene Autry. More than 25 years after his last starring role, Maynard returned to two small parts in films in 1970 and 1972, notably in The Marshal of Windy Hollow. His film career consisted of 109 films produced by Columbia, Universal, MGM, World Wide, Tiffany, Mascot, First National, Monogram and Astor.

emanship and rugged good looks made Maynard a cowboy star. His white stallion, "Tarzan", also became famous. He became one of the first singing cowboys with Columbia Records, recording two songs, "The Lone Star Trail" and "The Cowboy's Lament". With his white cowboy hat, fancy shirt, and pair of six-shooters, from the 1920s to the mid-1940s, Maynard appeared in more than 90 films. However, his alcoholism severely impacted his life and his career ended in 1944. He made appearances at state fairs and rodeos. He then owned a small circus operation featuring rodeo riders but eventually lost it to creditors. The significant amount of money he had earned vanished, and he lived a desolate life in a rundown mobile home. During these years, Maynard was supported by an unknown benefactor, long thought to be Gene Autry. More than 25 years after his last starring role, Maynard returned to two small parts in films in 1970 and 1972, notably in The Marshal of Windy Hollow. His film career consisted of 109 films produced by Columbia, Universal, MGM, World Wide, Tiffany, Mascot, First National, Monogram and Astor.

Ken Maynard at the Circus:

In 1936 Maynard bought wagons and rail cars from George Christy and organized the Ken Maynard Diamond Wild West Circus and Indian Congress. The show opened in Van Nuys, California and lasted a coupled of weekends. The following year he was featured with the Cole Brothers, Beatty Circus. He remained there in 1938 and then came back to Cole Brothers in 1940. In 1950 he appeared with the Biller Brothers Circus.

Timothy McCoy (1891-1978) was born in Saginaw, Michigan, but grew up on a ranch in Wyoming. He served as a Lt. Colonel in World War I. In 1926 he staged the "Winning of the West" at the Sesqui-Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. In 1942 he was the Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, but was defeated. His first film The Covered Wagon was made for Famous Players-Lasky Corporation in 1923. His film career consisted of 96 films produced by Universal, Columbia, MGM, Producers Releasing Corporation, Puritan, Victory Pictures Corp. and Embassy. McCoy’s best silent films were made for MGM as their top western actor. His last featured role was for Monogram in 1942. In 1965 at age 80 he was featured in Requiem for a Gun Fighter, produced for Embassy Pictures. A better-than-average shoot-'em-up western has professional gunfighter Cameron mistaken for a judge in a small town plagued by McNally and his henchmen. Only a local couple know his true identity, and they talk him into keeping the peace and staging the trial for one of the bad guys” The movie received good reviews—not bad for 80 years old.

Tim McCoy at the Circus:

In 1935 Sam Gumpertz hired McCoy to produce and star in a wild west show for Ringling-Barnum. He returned in 1936 and 1937. McCoy was paid $10,000.00 a week and he in turn paid all the other show personnel. Assuming that he was responsible for the big show crowds, McCoy made plans to tour his own wild west show in 1938. And what a beautiful show it was. New from rail cars to wagons, it was one of the finest new outfits to be introduced in the 20th century. In competition with Cole Brothers and Hagenbeck-Wallace, it opened at the International Amphitheater in Chicago on April 14th. Three big shows in one city did not allow any of them to do outstanding business. After ten days in Chicago McCoy’s forty blue and white rail cars made a Sunday run of 315 miles to open under canvas in Columbus, Ohio. One week later the show closed in Washington, DC where it was sold at auction. The venture cost McCoy $300,000, just about wiping him out. McCoy went back to Hollywood and more poverty row pictures. In spite of his age he again went back to the circus, this time with the Al G. Kelly & Miller Brothers in 1957. The following season he joined the Carson & Barnes Circus where he remained through 1961. During the first two months of the 1962 season McCoy appeared with the Hoxie-Bardex Circus. Later he partnered with Tommy Scott’s medicine show and remained for thirteen years.

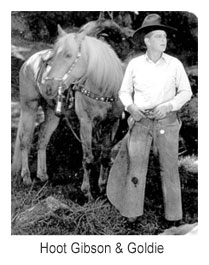

Edward Richard Gibson (Hoot Gibson 1892-1963 ) was the last of the big timers. He learned to ride a horse while still a very young boy. His family moved to California when he was seven years old and as a teenager he worked with horses on a ranch, which led to competition on bucking broncos. Given the nickname "Hoot Owl" by co-workers, the name evolved to just "Hoot". He was an accomplished rodeo performer by age sixteen. He too had outdoor show business experience prior to entering the movies.

boy. His family moved to California when he was seven years old and as a teenager he worked with horses on a ranch, which led to competition on bucking broncos. Given the nickname "Hoot Owl" by co-workers, the name evolved to just "Hoot". He was an accomplished rodeo performer by age sixteen. He too had outdoor show business experience prior to entering the movies.

In 1910, film director Francis Boggs (Selig Studios) was looking for experienced cowboys to appear in his silent film short, Pride of the Range. Gibson and another future star of western films, Tom Mix, were hired. After the director was killed by a deranged employee, Gibson was hired by director Jack Conway to appear in his 1912 Western, His Only Son. Acting for Gibson was then a minor sideline and he continued competing in rodeos to make a living. In 1912 he won the all-around championship at the famous Pendleton Round-Up and the steer roping World Championship at the Calgary Stampede. His film career lasted for 120 features. He worked for Selig, Universal RKO-Radio, Monogram and Screen Guild. In 1936 he was one of the top money western stars. His last film was made in 1947 by Screen Guild Pictures.

Hoot Gibson at the Circus:

Hoot Gibson was with Dick Stanley’s Congress of Rough Riders and Bud Atkinson’s Circus & Wild West in Australia. He competed in the Pendleton Round Up and the New York Stampede in 1916. Gibson was featured by Wallace Brothers Circus early in 1937 and then joined the Hagenbeck-Wallace show for the rest of the season. In 1938 he was with Robbins Brothers. In 1940 he organized the Hoot Gibson Rodeo and Thrill Circus. The show opened July 7 playing ball parks. It did not last long.

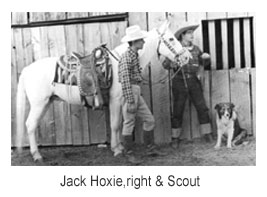

Jack Hoxie (John Hartford Hoxie 1885-1965) was born in Indian Territory. (later Oklahoma) After his father's death, his mother Matilda Hoxie (some reports list her as Cherokee) moved to Northern Idaho. At an early age, Jack became a working cowboy ranch hand. Matilda Hoxie married a rancher and horse trader named Calvin Scott Stone. The family then relocated to Boise where Jack worked as a packer for a U.S. Army Fort in the area, continuing to hone his skill as a horseback rider while competing in rodeos. In 1909 he met the performer Dick Stanley and joined his Wild West show. It was during this period that Jack met and married his first wife, Hazel Panting, who was a Western trick rider with the outfit. He won the National Riding Championship in 1914. His first movie job was as a stunt man. His first of 79 films was made in 1915. In 1926, Laemmle and Universal chose Jack to star as Buffalo Bill Cody in Metropolitan Pictures The last Frontier, co-starring William Boyd. The film would prove enormously commercially successful and Hoxie is often best recalled for his performance in the film. In 1927, however, Hoxie allegedly became dissatisfied with his contract at Universal and refused to renegotiate for another stint at the studio. Hoxie would continue throughout the later 1920s making films of lesser quality with lower budget film studios. He made his last silent film Forbidden Trail in 1929. His career faded quickly after sound, as even though he looked the part of a cowboy, his skills did not extend to sounding like one (He could barely read). He continued to appear, albeit in smaller roles, well into the 1930s finally quitting film in 1934 because he unable to memorize the dialogue required by the talkies.

a horseback rider while competing in rodeos. In 1909 he met the performer Dick Stanley and joined his Wild West show. It was during this period that Jack met and married his first wife, Hazel Panting, who was a Western trick rider with the outfit. He won the National Riding Championship in 1914. His first movie job was as a stunt man. His first of 79 films was made in 1915. In 1926, Laemmle and Universal chose Jack to star as Buffalo Bill Cody in Metropolitan Pictures The last Frontier, co-starring William Boyd. The film would prove enormously commercially successful and Hoxie is often best recalled for his performance in the film. In 1927, however, Hoxie allegedly became dissatisfied with his contract at Universal and refused to renegotiate for another stint at the studio. Hoxie would continue throughout the later 1920s making films of lesser quality with lower budget film studios. He made his last silent film Forbidden Trail in 1929. His career faded quickly after sound, as even though he looked the part of a cowboy, his skills did not extend to sounding like one (He could barely read). He continued to appear, albeit in smaller roles, well into the 1930s finally quitting film in 1934 because he unable to memorize the dialogue required by the talkies.

Jack Hoxie at the Circus:

Hoxie spent more time with the circuses than any other western star and was with more shows. He began in 1929 with the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West. In 1931 and 1934 he was with Schell Brothers. In 1933 and 1934 he was with Downie Bros. In 1935 he was with the Harley Stadler show and returned to Downie in 1936. In the spring of 1937 Cy Newton framed a new circus in Raymond, and induced Hoxie to invest in the show and be the feature. It was built new from the ground up. Titled Jack Hoxie’s Circus, it closed abruptly in July when Newton departed. Hoxie enlisted the help of R.M. Harvey and reopened the circus on July 31. Hoxie left the show in September and it quickly closed for the second time. Hoxie was back with Downie Brothers in 1938. In 1939 he was back with Lewis Brothers and with Bud Anderson in 1940. He ended his career with Mills Brothers in 1946 and 1947.

Buck Owens a champion rodeo performer, began his circus career with Sells-Floto Circus in 1927. He was with Robbins Brothers in 1930. He continued with Downie Brothers in 1932, then Hunts Circus in 1934. Owens came back to the sawdust arena with Si Rubens to tour with the Buck Owens Circus in 1946 and 1947. Although he was advertised as a famous western screen star, no mention has been found of him in motion picture references.

Buck Owens Show Different with Wild West Features; Horses Do Labor of Bulls.

Equine Motif Gives Program Spice – Personnel is Happy

By J. Edwards The Billboard, July 27, 1946

PERU, IND. July 20 – At first glance the Buck Owens Circus & Wild West appears to be like any other show of similar size. But start looking around this new outfit launched last spring by Buck Owens and Si Rubens and you find there are a number of things that are at least a little different. A couple of minor details catch the eye first on the midway. One is the side show banners somewhat arty in design and entirely devoid of lettering. The other is the office wagon which instead of being rear end out, is parked parallel with the midway, so the ticket windows are on the side.

Hoss Opry for True

Pass through the royal blue marquee and you find yourself in a hip-roof top, 60 by 100 feet that contains nothing but horses, horses, horses. Then it becomes apparent that this is perhaps the horsiest motorized show ever took to the road and that’s not overlooking the Tom Mix show of 10 years ago. Inside the big top the program gets under way when the opening number comes on with five horses and riders. Even a bigger surprise comes when the Liberty acts appear—three of them with six horses each. From a herd of “toy” horses in the side show, one is brought in for a track specialty and introduced as the world smallest Percheron (age 4 years, weight 40 pounds). And carrying the equine motif still further Buck Owens enters with his horse, Goldie, one of the horse rescue scenes which to the strains of soft music is altogether effective. Buck blows the whistle throughout and does a neat and concise job of announcing. At about the three quarter mark in the program he proclaims that this is a show that throws traditions to the winds, that whereas most shows save their cowboys and cowgirls for the end, this one presents them in the performance. Then the show really comes to life and finishes with life aplenty. Four couples in bright western togs do a quadrille on horseback with Buck doing the calling. Leon Snyder, son of Leo (Tiger Bill) Snyder next executes a series of horse catches. Then the three rings are given over to some really solid one-spinning by Snyder, Joe Shwika and Shorty Schenrer, each finishing with specialties. With them in the Wild West line-up are Alta (Mrs. Buck) Owens and Erma Niquette, Meulah Scherer, Novel Freeman and Harry (Junior) Rawls. The next turn out is for trick riding which brings the show to a fast finale.

The Spangled Section

Straight circus acts include the excellent trampoline work of the Morales family (four), Paul Walcott’s dogs featuring a wall-scaling Gordon settler, Paul and Ellen Knight on the high wire, Virginia Lynne’s chair balancing, the Kohl Trio’s juggling, and the usual assortment of swinging ladders, cloud swings and webs, the latter with special wardrobe. Acts throughout have a clean well-dressed appearance. The clowning of Joe, Sig and Charles allows the conventional bits of firecracker, hair-cutting, diaper, etc. Not once is the water gag used. John Dutch’s band of nine piece and calliope gives good old circus music. The big top is a 90 with three 40s (a popular size this season) and has nine-high blues all the way around. The canvas is white without colored trim, but bally cloths and seat ends of blue and red give a needed touch of color. Big show tickets are $1.20 for adults, 60 cents for kids and 60 cents for reserved. Concert and side show each gets 25 cents.

Concert and Side Show

Concert features are Stormy, a handsome white horse with a movie build-up, and H.S. (Professor) Gatchell, a grizzly old fugitive from the barber shop with a troupe of dogs, he cues entirely by voice over a mike. George Foster’s side show is houses under a push-up top that has a 35 foot round top with three 30s. Personnel includes Robert Reynolds, inside lecturer, Punch and Dwight, magic, Marjorie Marshall sword box, Thomas Whitehurst, human pincushion and fire, Professor Gatchell and Ray Garrison annex. There are also two cages of Monks, a baby buffalo, the “toy” horses, and a wild life exhibit supplied by Tommy Buchanan. Buchanan joined a month ago as a fixer, and his wife Patty, is handling press and kid marquee promotions ahead. Ethel Foster is on the tax box, while the Niquette girl’s mother Billie Grimes, lends her general personality to the front door. The show had an up and coming young lot superintendent in Charlie Grimes who was schooled by Ben and Eva Davenport. He was with the Davenport’s 10 years, from their Society Circus and Med Show days until he left Daily Bros. in 1943 to enter the navy.

Reconversion from the War

At one point in his announcements Buck Owens mentions the percentage of the show’s male personnel that served in the armed forces. Something that he omits is that he was a major in the Army Air force. Physically the show has several aspects of a war reconversion job under its red paint. The office, cook house, and two horse trucks were built from semi-trailer buses of the army. The sleepers were converted defense buses and the light paint is army surplus. The management hopes that the impending imports of elephants will sooner or later take care of the show’s deficiency in that respect. Meanwhile, lack of bulls for work is done by horses. Owen, in breaking his Liberty acts, showed foresight by using light Percheon stock for two of the groups. Two teams of the sorrels raise the poles and peaks of the big top, and the six blacks make up a hook-rope team to snake stuff off muddy lots.

Downhearted! No!

The Owens-Reuben combination appears to be a congenial and effective one, with Buck handling the back yard and Si the office. As is always the case with new shows, there have been plenty of grapevine rumors about this one, most of them are inaccurate as they are dire. It’s true the outfit received an extraordinary tough hazing from the weather, and it’s no secret that business all season has been pretty spotty. But if the partners are discouraged, they certainly don’t show it. The organization appears to be shot through with optimism and loyalty. And Owens observes that one sure way of maintaining loyalty is meeting pay days regularly. The partners say that in framing their show they allowed for the traditional rainy day, that they piled a sweet piece of money at their Shrine sponsored premier at Springfield, MO April 23-28 and that they managed to hold their own despite lack of any real business since. And with the show geared to make money, they say they are content to await the final returns in the fall before losing heart. Meanwhile, they are talking plans for the next season for what they call the coming show.

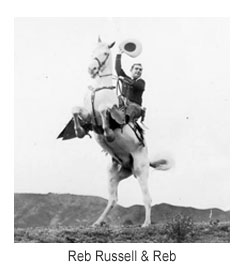

Lafayette H. “Reb” Russell (1905-1978) was a former All-American fullback at Northwestern University. It was inevitable that a big, good-looking, famous football star would be courted by Hollywood, and Russell was eventually given small parts in a few films at Fox Pictures, but nothing really came of them. However, he did sign a contract with independent producer Willis Kent to star in a series of low-budget westerns (1934-1935); Range Warfare, Fighting  Through, The Man from Hell, Fighting to Live, The Cheyenne Tornado, Border Vengeance, Outlaw Rule, Arizona Bad Man, Blazing Saddles, and Lighting Triggers. But low budget is perhaps a charitable description of them. For all his athletic prowess, riding ability and good looks, Russell just wasn't much of an actor, but even if he had been he wouldn't have been able to overcome the threadbare production values, lame and trite scripts and overall shoddiness of the films themselves. They were distributed through the states-rights syndication system, which meant that basically not a whole lot of people saw them, and Russell never really made an impression on either fans or Hollywood itself. By 1935 he and Kent had parted ways.

Through, The Man from Hell, Fighting to Live, The Cheyenne Tornado, Border Vengeance, Outlaw Rule, Arizona Bad Man, Blazing Saddles, and Lighting Triggers. But low budget is perhaps a charitable description of them. For all his athletic prowess, riding ability and good looks, Russell just wasn't much of an actor, but even if he had been he wouldn't have been able to overcome the threadbare production values, lame and trite scripts and overall shoddiness of the films themselves. They were distributed through the states-rights syndication system, which meant that basically not a whole lot of people saw them, and Russell never really made an impression on either fans or Hollywood itself. By 1935 he and Kent had parted ways.

Reb Russell at the Circus:

Reb Russell left Hollywood and toured with several traveling circuses. Russell Bros. Circus in 1936 and with Downie Brothers in 1937. In the 1940s he returned to Coffeyville, married and raised a family. He bought several ranches, becoming somewhat of an expert on livestock breeding.

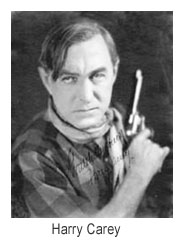

Harry Carey (Henry DeWitt 1878-1947) “Grew up on City Island, New York. Carey's love of horses was inculcated in him at a young age, as he watched New York City's mounted policemen go through their paces in the 1880s, which  prompted him to write a play, "Montana," about the Western frontier. He decided to star in his own creation, and the play proved a big success when mounted as a stock production in the middle of the decade. Audiences were thrilled by a bit of business where Carey brought his horse onto the stage.” “He began appearing in films for director D. W. Griffith, most memorably in The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1913), in which he played a hood in the Hoods of New York. Carey's movie acting career was safely launched at Biograph's studios in the Bronx, and he would eventually appear in almost 250 motion pictures and became a big star in silent Westerns. Carey's cowboy persona with its taciturn expression has been linked to that of the dour William S. Hart, the first Western superstar. Hart's gritty Westerns, like Carey's, emphasized realism. Carey did not dress as flashily as Ken Maynard or the great Tom Mix, and his films were often true portrayals of the West instead of Mix's flashy horse operas. Good with physical business, particularly involving his hands, he developed signature gestures such as the way he sat a horse, a semi-slouch with his elbows resting on the saddle horn. His biggest film was with MGMs Trader Horn 1931. Carey was with the Barnett circus in 1944.

prompted him to write a play, "Montana," about the Western frontier. He decided to star in his own creation, and the play proved a big success when mounted as a stock production in the middle of the decade. Audiences were thrilled by a bit of business where Carey brought his horse onto the stage.” “He began appearing in films for director D. W. Griffith, most memorably in The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1913), in which he played a hood in the Hoods of New York. Carey's movie acting career was safely launched at Biograph's studios in the Bronx, and he would eventually appear in almost 250 motion pictures and became a big star in silent Westerns. Carey's cowboy persona with its taciturn expression has been linked to that of the dour William S. Hart, the first Western superstar. Hart's gritty Westerns, like Carey's, emphasized realism. Carey did not dress as flashily as Ken Maynard or the great Tom Mix, and his films were often true portrayals of the West instead of Mix's flashy horse operas. Good with physical business, particularly involving his hands, he developed signature gestures such as the way he sat a horse, a semi-slouch with his elbows resting on the saddle horn. His biggest film was with MGMs Trader Horn 1931. Carey was with the Barnett circus in 1944.

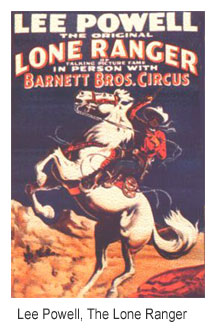

Lee Powell (1908-1944) After circus stock work he tried his luck in Hollywood making his first appearance (uncredited)  in Under Two Flags. Powell gained fame for playing the suspect who turned out to be The Lone Ranger and one of “The Fighting Devil Dog”, a 1938 serial”, a Western for the soon to be defunct National Pictures and made the six Western programmer films of the Frontier Marshals series. As a contract Republic player he received $150 a week. Powell wanted more money for a second Lone Ranger serial. Republic said no, hiring Robert Livingston for the part. Powell moved to National Pictures making B serials. (1939) With no more film work in the offering, he joined the Barnett Brothers circus being billed as the original Lone Ranger until litigation over the original copyright owners had him change his billing. The Lone Ranger name was owned by the Lone Ranger, Inc. It started on a Detroit radio station in the early 1930s. The company placed a Lone Ranger, played by an unidentified person, on the Olympia Circus, operated by the Chicago Stadium Corporation in Chicago and Detroit in 1941. There Powell met and married Norma Rogers, a circus bareback rider and the daughter of the circus owner. Returning to Hollywood he had a part in a Flash Gordon series at Universal. His final pictures were made by Producers Releasing Company in 1941 and 1942.

in Under Two Flags. Powell gained fame for playing the suspect who turned out to be The Lone Ranger and one of “The Fighting Devil Dog”, a 1938 serial”, a Western for the soon to be defunct National Pictures and made the six Western programmer films of the Frontier Marshals series. As a contract Republic player he received $150 a week. Powell wanted more money for a second Lone Ranger serial. Republic said no, hiring Robert Livingston for the part. Powell moved to National Pictures making B serials. (1939) With no more film work in the offering, he joined the Barnett Brothers circus being billed as the original Lone Ranger until litigation over the original copyright owners had him change his billing. The Lone Ranger name was owned by the Lone Ranger, Inc. It started on a Detroit radio station in the early 1930s. The company placed a Lone Ranger, played by an unidentified person, on the Olympia Circus, operated by the Chicago Stadium Corporation in Chicago and Detroit in 1941. There Powell met and married Norma Rogers, a circus bareback rider and the daughter of the circus owner. Returning to Hollywood he had a part in a Flash Gordon series at Universal. His final pictures were made by Producers Releasing Company in 1941 and 1942.

Bill Cody (William Joseph Jr. 1891-1948) Immediately out of college, he joined the

Metropolitan Stock Company, touring the U.S. and Canada. This eventually led him to Hollywood. In 1922 he began working as a stuntman after some stage and rodeo experience. Be a bit careful here as he was known as the real Bill Cody not to be confused with Buffalo Bill Cody. Independent Pictures signed him an eight series film deal for the 1924-1925 season. Jesse Goldburgs's company, Independent Pictures, although known for being made for as little money as possible, had gained a good reputation for having good casting and locations for their films. The first of the series starring Cody was Dangerous Days, followed by The Fighting Sheriff. Following the Independent Pictures series, Cody starred in two films, The Galloping Cowboy and King of the Saddle, both released in 1926. That same year he starred in Arizona Whirlwind. He starred in Born to Battle, (1927), which gave him an opportunity to exhibit his horse riding skills and to use a bull whip on screen, and two more Bill Cody Productions boasting stories supposedly concocted by Cody himself: Gold From Weepah and Laddie, Be Good. Agile and pleasant in appearance, Cody ended his silent film career by starring in a group of action pictures released by Universal which temporarily removed him from the western milieu. His first talking feature was Under Texas Skies, starring Bob Custer in 1930. When the talkies started he survived the change despite his well-known difficulty with the memorization of dialogue. He spent most of his career working for the most impoverished poverty row studios, with hack scripts and starvation budgets. Aficionados of the genre have cited Cody's The Border Menace, (1934) as the worst B western ever made. By the late 1930s Cody's starring days were over and he was doing bits in "Stagecoach" (1939) and the Republic serial.

Bill Cody at the Circus:

James Heron’s 1932 Walter L. Main Circus featured Cody. The Cody Ranch Wild West name was added to the title in May. By late June it was Bill Cody Ranch Wild West. By August the title became Bostock’s Circus and Cody Wild West. By September it was back to Walter L. Main and Cody Ranch Wild West. Cody was the Downie Bros. western star in 1935.

Buzz Barton (1914-1980) also used the stage names: Billy Lamar, Billy Lamoreaux and Red Lennox. He was discovered at Cheyenne Frontier Days in 1927. He made his first western movie at age ten and was known as the boy  stunt rider for Film Booking Office studios. He has two uncredited stunts; Silver on the Sage in 1938 and The Mexicali Kid (stunt double) in 1938. He has 27 uncredited parts in films almost all of them after 1936 and 38 film credits. He also had a part as the horse wrangler (uncredited) in The Shootist. The Last Defender (1934) is still listed as active footage.

stunt rider for Film Booking Office studios. He has two uncredited stunts; Silver on the Sage in 1938 and The Mexicali Kid (stunt double) in 1938. He has 27 uncredited parts in films almost all of them after 1936 and 38 film credits. He also had a part as the horse wrangler (uncredited) in The Shootist. The Last Defender (1934) is still listed as active footage.

Red Ryder has become synonymous with Daisy, BB guns and American youth. It wasn't the first BB gun to be named for a personality. That distinction goes to Buzz Barton. In 1932, Daisy signed circus performer Buzz Barton to put his name on a special BB gun. A year later, Daisy got it exactly right. The second Buzz Barton was quite different from all other Daisy’s of the time. It was the first to feature a branded stock with Buzz Barton burned into the left side of the butt inside a star frame. The Buzz Barton had much of the early 20th century about it. The lever was cast iron and worked in the old-style short cocking stroke that made men out of small boys. It was harder to cock, but that was part of the passage to manhood!

Buzz Barton at the Circus:

Buzz Barton at the Circus:

In 1933 Buzz Barton was featured on Heron’s Walter L. Main Circus. The Main title was inactive during the 1929 season, but in 1930 William "Honest Bill" Newton used the title on a truck circus. This was interesting because it was one of the few times in circus history that a circus title had been used on a wagon show, a rail show and a truck show.

James Heron operated a truck show in 1931, and called it Walter L. Main. The famous Hanneford Family was featured with the Heron show that year. At the beginning of the 1932 season the Heron show was titled Walter L. Main featuring Bill Cody. Later in the season the show used the Bill Cody Ranch Wild West title, and still later in 1932 it was called Bostock's Wild Animal Circus and Cody Wild West. Main was anxious to make a deal with any circus operator and in 1933 he arranged for the use of his title on a truck show operated by Tom Gorman.

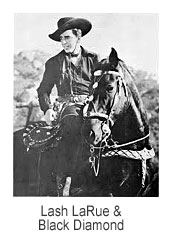

Lash LaRue (1917-1996) He looked so much like superstar Humphrey Bogart that character actress Sarah Padden asked if the two were related. LaRue said he didn't think so. After a long pause studying the young actor's face, she asked, "Did your mother ever meet Humphrey Bogart?" His debut Song of Old Wyoming (1945), headlined singing cowboy Eddie Dean and co-starred the beautiful Jennifer. LaRue, with his remarkable resemblance to Bogart, certainly looked the part and was cast after claiming he'd worked a bullwhip since childhood. In fact he had never handled one, so after he was cast he ran out and borrowed a whip. He spent the next several days trying to learn to use it, but wound up beating himself senseless and bloody, and was finally forced to admit to Tansey that he didn't know what he was doing. Impressed by LaRue's sincerity and laughing at his injuries, Tansey arranged for personalized bullwhip instruction, a rather lavish expense for penny-pinching Producers Releasing Corporation. This picture was also unique in being PRC's first western to be shot in color, albeit in Cinecolor, a process favored by low-budget producers because it was much cheaper than the better known (and more garish) Technicolor, even though it was decidedly inferior and gave films shot in it an anemic, washed-out look. Although he wasn't the star, and billed as "The Cheyenne Kid," LaRue received a relatively large amount of fan mail and it dawned on the powers-that-be at PRC that they had a potential star on their hands. Not wanting to mess with a good thing, the studio paired the whip-cracking LaRue with the singing Dean two more times before splitting them off into their own pictures. LaRue quickly adopted an all-black wardrobe and rode a jet black horse to accentuate his image as a bad guy/good guy, sort of an early western anti-hero. He became "King of the Bullwhip" and a solid staple of Saturday-afternoon matinées. Despite having one of the more recognizable names in B-westerns, he never ranked among the top stars in popularity polls, probably attributable less to his screen persona or acting ability and more to his films' awful scripts and deplorable lack of production values due to PRC's legendary cheapness, a factor that hurt the careers of many of the studio's western stars. LaRue almost always performed his own stunts—mainly because PRC was loathe to spend money on professional stunt men, who in those days demanded higher pay than the stars they were doubling for—a fact he took pride in and made sure that he "conveniently" lost his hat during action scenes so his audience could see that it was actually him in the fray and not a stunt double. He is credited with 40 actor parts in film and 28 parts in his own TV series Lash of the West (1953). This 15-minute show consisted of cowboy actor Lash LaRue introducing clips from his old films and occasionally bringing on a guest, usually an actor who appeared in one of more of his pictures. And there were Lash LaRue comic books. The first issue was quarterly, then bimonthly, then monthly. Then came a comic called Six Gun Heroes which featured Lash LaRue on the cover more than fifty percent of the time. "I used to get royalties from the comics which bought me a new car every year-—a Cadillac. I grew up a poor boy—I had to find out what you could do with money."

Impressed by LaRue's sincerity and laughing at his injuries, Tansey arranged for personalized bullwhip instruction, a rather lavish expense for penny-pinching Producers Releasing Corporation. This picture was also unique in being PRC's first western to be shot in color, albeit in Cinecolor, a process favored by low-budget producers because it was much cheaper than the better known (and more garish) Technicolor, even though it was decidedly inferior and gave films shot in it an anemic, washed-out look. Although he wasn't the star, and billed as "The Cheyenne Kid," LaRue received a relatively large amount of fan mail and it dawned on the powers-that-be at PRC that they had a potential star on their hands. Not wanting to mess with a good thing, the studio paired the whip-cracking LaRue with the singing Dean two more times before splitting them off into their own pictures. LaRue quickly adopted an all-black wardrobe and rode a jet black horse to accentuate his image as a bad guy/good guy, sort of an early western anti-hero. He became "King of the Bullwhip" and a solid staple of Saturday-afternoon matinées. Despite having one of the more recognizable names in B-westerns, he never ranked among the top stars in popularity polls, probably attributable less to his screen persona or acting ability and more to his films' awful scripts and deplorable lack of production values due to PRC's legendary cheapness, a factor that hurt the careers of many of the studio's western stars. LaRue almost always performed his own stunts—mainly because PRC was loathe to spend money on professional stunt men, who in those days demanded higher pay than the stars they were doubling for—a fact he took pride in and made sure that he "conveniently" lost his hat during action scenes so his audience could see that it was actually him in the fray and not a stunt double. He is credited with 40 actor parts in film and 28 parts in his own TV series Lash of the West (1953). This 15-minute show consisted of cowboy actor Lash LaRue introducing clips from his old films and occasionally bringing on a guest, usually an actor who appeared in one of more of his pictures. And there were Lash LaRue comic books. The first issue was quarterly, then bimonthly, then monthly. Then came a comic called Six Gun Heroes which featured Lash LaRue on the cover more than fifty percent of the time. "I used to get royalties from the comics which bought me a new car every year-—a Cadillac. I grew up a poor boy—I had to find out what you could do with money."

Art Mix (1896-1972) starred in a few B western films as the hero for a brief time. His starring silent and talkies low budget productions such as the Ace of Cactus Range (1924), showed him as a young god-looking cowboy. He slipped into a henchman/gang member and town-drunk roles, often uncredited. He must have had some talent as he was usually higher on the bad-guy list. In his silents as well as later henchman roles in talkies, he wore a tall hat, probably to disguise his short height and give the impression that he was taller. His filmography lists 175 sound era films, of which 157 are westerns and 17 are movie serials.

Art Mix With the Circus:

Art was featured with Kay Brothers Circus 1937. The Kay Brothers Circus had only a single elephant in its first season of 1932, but later acquired another and they were presented by Ketrow's daughter, Mary Ellen Buckles Woodcock. Tina Cuccia said that her father, Nick Cravat, and Burt Lancaster lived in the same neighborhood with Nick living with the Italians and Burt in the Irish section. Cravat was a stage name as Cuccia was too hard to pronounce. His two daughters preferred Cravat as kids since Cuccia was pronounced as coo-chi (on purpose naturally in grade school) and the embarrassment was more than two little girls could bear. Once Burt and Nick learned some tricks and developed and act and they joined the Kay Brothers Circus. Their act which began on a single bar, later evolved into a comic horizontal act (two bars situated about eight feet apart) in which they went from bar to bar performing summersaults, giant swings and of course a little comedy. Often the routine was performed in street clothes, other times in tights. Another spectacular feat that they mastered was Burt climbing up a pole that Nick balanced on his forehead. Art was also with the Cole Brothers in 1941 and the short lived Terrell Jacobs show in 1944. He was the star of the short lived Buffalo Wild West in 1947.

Art was featured with Kay Brothers Circus 1937. The Kay Brothers Circus had only a single elephant in its first season of 1932, but later acquired another and they were presented by Ketrow's daughter, Mary Ellen Buckles Woodcock. Tina Cuccia said that her father, Nick Cravat, and Burt Lancaster lived in the same neighborhood with Nick living with the Italians and Burt in the Irish section. Cravat was a stage name as Cuccia was too hard to pronounce. His two daughters preferred Cravat as kids since Cuccia was pronounced as coo-chi (on purpose naturally in grade school) and the embarrassment was more than two little girls could bear. Once Burt and Nick learned some tricks and developed and act and they joined the Kay Brothers Circus. Their act which began on a single bar, later evolved into a comic horizontal act (two bars situated about eight feet apart) in which they went from bar to bar performing summersaults, giant swings and of course a little comedy. Often the routine was performed in street clothes, other times in tights. Another spectacular feat that they mastered was Burt climbing up a pole that Nick balanced on his forehead. Art was also with the Cole Brothers in 1941 and the short lived Terrell Jacobs show in 1944. He was the star of the short lived Buffalo Wild West in 1947.

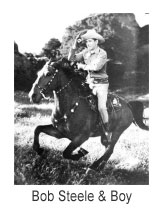

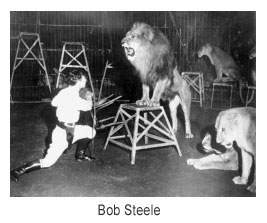

Bob Steele (1906-1988) began making films at age 14, co-starring with his brother in a series of "outdoors" short  subjects produced and directed by his filmmaker father, Robert N. Bradbury. Gaining popularity in B western series of the silent movies and early talkie era. Steele was in With Davy Crockett at the Fall of the Alamo in 1926. Most of his films shared the same plot: Steele's character was forever searching for the murderer of his father, perhaps significantly, as many of Steele's starring vehicles were scripted by his real-life dad. His short stature and scrappy nature were things that many young western fans could identify with (and the fact that most of the villains he beat up were much bigger than he was didn't hurt, either). By the 1940s his career was on the decline, accepting supporting roles in many big movies such as John Wayne movies; Island in the Sky, Rio Bravo and Rio Lobo. He often ventured into other genres, and gave acclaimed performances such as Of Mice and Men (1939) (an adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel), receiving some of the best reviews of his career as the sadistic Curley. He was in in the

subjects produced and directed by his filmmaker father, Robert N. Bradbury. Gaining popularity in B western series of the silent movies and early talkie era. Steele was in With Davy Crockett at the Fall of the Alamo in 1926. Most of his films shared the same plot: Steele's character was forever searching for the murderer of his father, perhaps significantly, as many of Steele's starring vehicles were scripted by his real-life dad. His short stature and scrappy nature were things that many young western fans could identify with (and the fact that most of the villains he beat up were much bigger than he was didn't hurt, either). By the 1940s his career was on the decline, accepting supporting roles in many big movies such as John Wayne movies; Island in the Sky, Rio Bravo and Rio Lobo. He often ventured into other genres, and gave acclaimed performances such as Of Mice and Men (1939) (an adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel), receiving some of the best reviews of his career as the sadistic Curley. He was in in the  western TV comedy series F Troop (1965-1967) playing the part of Trooper Duffy, who at the drop of a hat would began reminiscing about his fighting at the Alamo and fought "shoulder to shoulder” with Davy Crockett and was the self-styled sole survivor of the Alamo. He appeared in 150 films over his 50 year career and numerous TV productions.

western TV comedy series F Troop (1965-1967) playing the part of Trooper Duffy, who at the drop of a hat would began reminiscing about his fighting at the Alamo and fought "shoulder to shoulder” with Davy Crockett and was the self-styled sole survivor of the Alamo. He appeared in 150 films over his 50 year career and numerous TV productions.

Bob Steele at the Circus:

Clyde Beatty started the Clyde Beatty Circus (1944) a huge endeavor traveling by rails and featuring the best performers in the world of the circus. Bob Steele was featured with the circus during the early part of the 1950 season. Beatty became famous for his "fighting act," in which he entered the cage with wild animals with a whip and a pistol strapped to his side. The act was designed to showcase his courage and mastery of the wild beasts, which included lions, tigers, and hyenas, sometimes brought together all at once in a single cage in a potentially lethal combination.

Doug Autry, (1922-??) a brother of Gene Autry. Doug, was featured by Dailey Brothers Circus in 1949 and by Clyde Beatty Circus in 1955. They put up big signs with “Autry” on it. Most were disappointed when they saw it was Doug, not Gene. But the little kids asked for his autograph just because he was related to Gene. Although Autry was advertised as a movie cowboy no reference has been found of his appearing in a film. The circuses were well known for coming up with some unique exaggerations in their promotions.

Then again film is not much better. The old series shown in the movie theaters always had the hero just about to be killed at the end. The next week by some miracle the hero was in a much better predicament. Nearly all of the western stars, most born in the 1890s, were in the declining years of their motion picture careers when they were with the circus. Many found work at poverty row producers like Resolute, Majestic, Freuler, Argosy, Mascot, World Wide, Embassy and Screen Guild. Some of these cheap B westerns were made in as little as five days. The silent movies were shot on highly flammable 35mm nitrate film. As the film gets older it becomes explosive. To tell if the film is nitrate hold a short piece in a pliers and put a match to it. If nitrate flashes rather than burns it is nitrate. Anything like that should be turned over to the Margaret Herrick Library, division of the MPAA. The oxidized film can also go off by heat or shock. The film can be stabilized by “washing” it in nitrogen. At best a few are restored each year depending on who was in the film or who directed it. The process is very expensive. The posters for the B westerns were printed on pulp paper which lots of acid it in. They were folded and went with the film to the next stop. As the paper ages it turns dark brown and brittle. Someone like Studio C can restore them, but you are talking sincere money. The restoration of a Buck Jones 3 sheet poster ran $895. Restoring the old PR photos is also equally hard and expensive. If memory is still working, the restoration of a badly tattered water stained b/w photo ran about $1,200. I should have tossed it but there were no other known copies. If you are trying to figure out what really happened to the cowboys, that is very subject to the imagination of the PR department and most material is gone. —Author

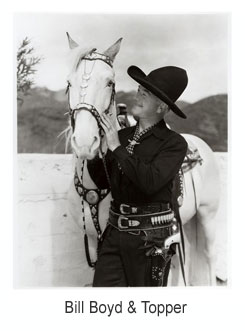

William Boyd 1895-1972 grew up in Oklahoma. Following his father's death, he moved to California and worked as an  orange picker, surveyor, tool dresser and auto salesman. He went to Hollywood in 1919, already gray-haired. His first role was as an extra in Cecil B DeMille’s Why Change Your Wife (1920), and other silent movies such as The Temple of Venus (1923), The Midshipman (1925), and The Volga Boatman (1926) where he had the leading romantic role, thus quickly becoming a matinée idol and earning upwards of $100,000 a year. In an early movie Hoppy kissed Evelyn Brent on the forehead as she was dying. His fans saw this as unmanly, so all future romance was left to his partners, and there was a different leading lady in each picture. With the end of silent movies, Boyd was without a contract, couldn't find work and was going broke. By mistake his picture was run in a newspaper story about the arrest of another actor with a similar name William “Stage” Boyd on gambling, liquor and morals charges, hurting his career. In 1935 he was offered the lead role in Hop-a-long Cassidy, named because of a limp caused by an earlier bullet wound. He changed the original pulp-fiction character to its opposite, made sure that "Hoppy" didn't smoke, drink, chew tobacco or swear, rarely kissed a girl and let the bad guy draw first. By 1943 he had made 54 Hopalong Cassidy movies. In 1948 Boyd, in a savvy and precedent-setting move, bought the rights to all his pictures. He had to sell his ranch to raise the money, just as TV was looking for Saturday-morning Western fare. By 1950 he was the hottest name in television. The last film that he was in was in a cameo role riding his white horse "Topper" during the circus parade inside the tent of the movie The Greatest Show on Earth (1952). His filmography consists of 140 titles which includes the TV series.

orange picker, surveyor, tool dresser and auto salesman. He went to Hollywood in 1919, already gray-haired. His first role was as an extra in Cecil B DeMille’s Why Change Your Wife (1920), and other silent movies such as The Temple of Venus (1923), The Midshipman (1925), and The Volga Boatman (1926) where he had the leading romantic role, thus quickly becoming a matinée idol and earning upwards of $100,000 a year. In an early movie Hoppy kissed Evelyn Brent on the forehead as she was dying. His fans saw this as unmanly, so all future romance was left to his partners, and there was a different leading lady in each picture. With the end of silent movies, Boyd was without a contract, couldn't find work and was going broke. By mistake his picture was run in a newspaper story about the arrest of another actor with a similar name William “Stage” Boyd on gambling, liquor and morals charges, hurting his career. In 1935 he was offered the lead role in Hop-a-long Cassidy, named because of a limp caused by an earlier bullet wound. He changed the original pulp-fiction character to its opposite, made sure that "Hoppy" didn't smoke, drink, chew tobacco or swear, rarely kissed a girl and let the bad guy draw first. By 1943 he had made 54 Hopalong Cassidy movies. In 1948 Boyd, in a savvy and precedent-setting move, bought the rights to all his pictures. He had to sell his ranch to raise the money, just as TV was looking for Saturday-morning Western fare. By 1950 he was the hottest name in television. The last film that he was in was in a cameo role riding his white horse "Topper" during the circus parade inside the tent of the movie The Greatest Show on Earth (1952). His filmography consists of 140 titles which includes the TV series.

William Boyd at the Circus:

In 1950 Arthur Wirtz, owner of the Chicago Stadium, operated Cole Brothers Circus which featured Hopalong Cassidy.

The Cole Brothers Circus was started in 1906 and was named after W.W. “Chillie Billie” Cole, the first man to make one-million dollars in the circus business. On Feb, 20,, 1941, the winter quarters suffered one of the worst circus fires in history burning the winter quarters to the ground. There was no loss of human life but over 18 animals died; 2 elephants, 2 zebras, 2 llamas, 6 lions, leopards, 2 audads, a sacred Indian cow, a pigmy hippo and an unknown amount of monkeys. Circus tents were coated with paraffin wax dissolved in gasoline, a common waterproofing method of the time. If the tent caught fire, the flames spread rapidly melting the paraffin, which rained down like napalm from the roof. The Hartford Circus fire in 1944, occurred during an afternoon performance of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus attended by approximately 7,000 people. People stampeded toward the exit they entered from. Unfortunately, this was the end the fire was on. Fire had not spread to the other end and employees tried directing them to that exit. In the panic, crowds still stampeded the end on fire. Three minutes later the tent poles started collapsing and the roof—what was left—caved in. In six minutes total, almost all of the tent was burned and the area nothing more than smoldering ashes.

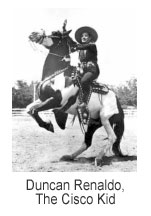

Duncan Renaldo (1904-1980) as The Cicso Kid

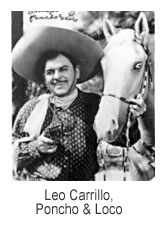

Leo Carrillo (1880-1961) as Poncho

Duncan Renaldo said his first childhood memories were in Romania. He emigrated to America in the 1920s. Failing to support himself as a portrait painter, he tried producing short films. He eventually took up acting and signed with MGM in 1928 where he worked in at least two? major films. In 1934, he was arrested for illegal entry into the United States, but eventually was pardoned by President Franklin Roosevelt and returned to acting, in poverty row studios. In 1945 he began the Cisco Kid western film series and transferred the character successfully to TV in the early 1950s, a popular western half hour television series (filmed in color) that ran until 1956. The Cisco Kid roamed the old west with his “black-and-white horse named Diablo, accompanied by his constant companion, Pancho, played by Leo Carrillo who was 24 years Renaldo's senior. The Cisco Kid always helped where needed, and unlike most Western heroes, rarely killed anyone. In movies and television, the Cisco Kid was depicted as a heroic Mexican caballero even though he was originally a cruel outlaw in the comics.

Duncan Renaldo said his first childhood memories were in Romania. He emigrated to America in the 1920s. Failing to support himself as a portrait painter, he tried producing short films. He eventually took up acting and signed with MGM in 1928 where he worked in at least two? major films. In 1934, he was arrested for illegal entry into the United States, but eventually was pardoned by President Franklin Roosevelt and returned to acting, in poverty row studios. In 1945 he began the Cisco Kid western film series and transferred the character successfully to TV in the early 1950s, a popular western half hour television series (filmed in color) that ran until 1956. The Cisco Kid roamed the old west with his “black-and-white horse named Diablo, accompanied by his constant companion, Pancho, played by Leo Carrillo who was 24 years Renaldo's senior. The Cisco Kid always helped where needed, and unlike most Western heroes, rarely killed anyone. In movies and television, the Cisco Kid was depicted as a heroic Mexican caballero even though he was originally a cruel outlaw in the comics.

The Cisc